New Dietary Ingredient Notification System Divides FDA, Supplement Industry

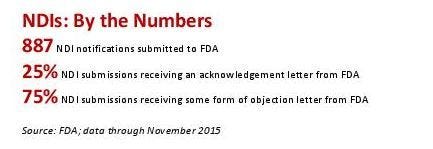

Since the passage of the 1994 law that governs dietary supplements, the majority of new dietary ingredient (NDI) notifications have been met with some type of an objection by FDA, such as a finding that there is inadequate safety data.

This blog is the first in a series of articles examining the FDA notification system that applies to new dietary ingredients.

For two decades, dietary supplement manufacturers bringing new substances to market have been required to notify FDA 75 days in advance. The notification system—and FDA’s interpretation of it—has divided the dietary supplement industry and regulators, causing disagreements about the scope of the requirements and when they are triggered.

Since the passage of the 1994 law that governs dietary supplements, three out of four new dietary ingredient (NDI) notifications have been met with some type of an objection by FDA, such as a finding that there is inadequate safety data or the company failed to sufficiently describe the ingredient, INSIDER has learned.

“I think the general view is the system has never worked very well," said Michael McGuffin, president of the American Herbal Products Association (AHPA), an organization that closely tracks NDI notifications. “The founders intended to have a straightforward mechanism to ensure that ingredients are safe."

The consensus is far from unanimous that the mechanism is either straightforward or even sufficient to ensure the safety of dietary ingredients. Of the 887 NDI notifications that FDA received through early November 2015, FDA objected to approximately 75 percent, according to FDA spokeswoman Marianna Naum.

George Burdock, Ph.D., whose company Burdock Group Consultants assists the industry with NDI notifications, attributed the high number of objections to several factors, including what he characterized as “drug claims made in the submission or defective labels" and “amateurish submissions." For instance, Burdock referenced a number of submissions that included foreign language publications without an English translation. Other submissions insufficiently described the type of extract, poorly identified the substance obtained from a plant, or failed to include adequate safety documentation, he explained in an email to INSIDER.

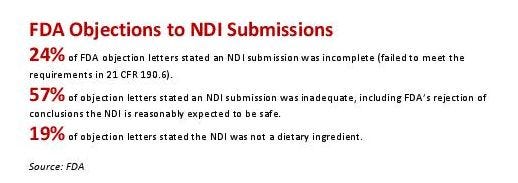

Of the objections raised by FDA in letters responding to NDI notifications, 24 percent represented a finding that the submission was incomplete, Naum noted. The agency objects more than twice as often on the ground that an NDI notification is inadequate, such as a finding refuting conclusions that the NDI is reasonably expected to be safe.

Under the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994 (DSHEA), the manufacturer or distributor of an NDI must provide evidence to FDA “establishing that the dietary ingredient when used under the conditions recommended or suggested in the labeling of the dietary supplement will reasonably be expected to be safe." In spite of the statute, FDA has applied a higher safety standard to NDI submissions, argued Burdock and Robert McQuate, Ph.D., co-founder and senior vice president of GRAS Associates LLC.

The higher standard—“reasonable certainty of no harm"—is rooted in a 1958 law, which created an exemption from premarket approval of food additives and authorized the introduction of new food ingredients that are so-called GRAS (generally recognized as safe).

McQuate said FDA has favorably viewed a far greater percentage of GRAS submissions than NDI submissions. He finds that noteworthy since NDIs are subject to a lesser safety standard than GRAS food ingredients.

McQuate said FDA has favorably viewed a far greater percentage of GRAS submissions than NDI submissions. He finds that noteworthy since NDIs are subject to a lesser safety standard than GRAS food ingredients.

As of Sept. 30, 2015, 81 percent of FDA’s responses to GRAS notices represented a so-called “good day letter" in which the agency had no questions about the submission; the agency only submitted a “bad day letter" in 3 percent of the cases. In 16 percent of FDA’s responses to GRAS submissions, the agency reported that the notifier had withdrawn the GRAS notice.

“The congressional intent was to have a standard that compromises nothing in safety, but establishes a lesser regulatory burden for supplement ingredients" than food ingredients, McGuffin of AHPA said. “But FDA hasn’t interpreted it that way."

Burdock described as “draconian" a safety threshold that he said was established by FDA in its July 2011 NDI guidance. FDA has been planning to issue a revised document in response to criticisms and questions from industry about the previous guidance.

“The draft guideline immediately set up an adversarial relationship between the submitter and the agency," Burdock said. Such an adversarial relationship has been blamed for giving firms little incentive to file the required NDI notification.

“When one submits in good faith information to FDA [the] hope is there will be reasonable interaction to achieve success, and these statistics are suggesting otherwise," said McQuate, whose regulatory career commenced within FDA’s GRAS Review Branch in 1977. “There is not a high and obvious incentive to share information with FDA when there are impediments and rejections and disadvantages, and we need to address that to preserve and improve the public health."

In response to the above criticisms, FDA has pointed out the NDI process is a requirement, “not an incentivization."

“Second, FDA reviewers take their review of the NDINs [NDI notifications] seriously, but there are hundreds of submissions that have met with an acknowledgment response as well," FDA spokeswoman Siobhan DeLancey said in an email. “The percentage of submissions receiving a ‘good day letter’ is even higher for those submitters that started with a pre-meeting with FDA reviewers."

McGuffin said companies have a higher success rate if they retain experts who are knowledgeable about the NDI notification process.

“That often means two consultants," McGuffin said, “an attorney and a toxicologist."

Daniel Fabricant, Ph.D., whose previous tenure as FDA’s top supplement official coincided with the issuance of the 2011 NDI guidance, said the industry should not be fearful of making submissions. Even if FDA disagrees with the safety data, a company that has made a complete submission has a strong argument that it has fulfilled its obligations under the NDI regulation (21 CFR 190.6). The law established a notification system for new ingredients rather than premarket approval.

DSHEA specifies FDA must prove a dietary supplement is unsafe, which is harder to establish than showing an NDI notification hasn’t been submitted at all or is incomplete. Several industry lawyers were not aware of a court case in which FDA filed a lawsuit to remove an NDI from the market after a company filed a notification and was met with an objection from regulators.

“It’s a notification process," Fabricant, executive director and CEO of the Natural Products Association (NPA), said in a phone interview. “As an industry, we shouldn’t be scared of a notification process."

Underreporting of NDIs

Even so, regulators and industry leaders suspect at least some companies are failing to submit NDI notifications, though the extent of underreporting is difficult to pinpoint. While FDA has received just 755 unique NDIs (excluding one or more resubmissions for the same ingredient) through Nov. 2015, the agency estimated there are more than 85,000 dietary supplements on the market.

“We have generally stated we believe NDIs are ‘under-notified,’ but this is difficult to verify," DeLancey, the FDA spokeswoman, said. “Due to our statutory authority, which is largely post market by design, if firms don’t do their due diligence and submit a NDIN before going to market, FDA has to track down the product, identify the ingredients, and make the determination it requires a notification before taking any action. FDA’s ability to conduct this activity is dependent on other competing priorities and limited resources."

Dietary supplement companies typically don’t issue a press release when they are bringing a new substance to market, and FDA doesn’t maintain a list of the dietary ingredients that are exempt from an NDI notification because they were marketed before Oct. 15, 1994.

In a 2010 testimony before the U.S. Senate’s Special Committee on Aging, an FDA official said the absence of an authoritative list on grandfathered ingredients under DSHEA makes it challenging for FDA to enforce the NDI provision.

“There is not a database of new dietary ingredients," McGuffin said. “Is there underreporting? I think there is probably underreporting … There is underreporting in every regulatory system."

McGuffin and other industry leaders questioned FDA’s estimate on the total number of dietary supplements in the market. INSIDER reached out to IRI and Nielsen, two market research firms that track the industry, but neither firm could provide a figure on the number of products in the market.

The Office of Dietary Supplements (ODS) and the National Library of Medicine at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) have created a database for dietary supplement labels for products that are marketed in the United States. The database houses more than 50,000 dietary supplement product labels. But ODS does not track the number of NDIs in the marketplace.

Industry leaders said FDA’s figure on the estimated number of dietary supplements in the market is potentially misleading and irrelevant to the number of NDIs.

“This number–85,000–is talking about every bottle of every brand," said Steve Mister, president and CEO of the Council for Responsible Nutrition (CRN), in a phone interview. “A great deal of these products are just different combinations of grandfathered ingredients."

Still, Mister acknowledged failing to make an NDI submission is a serious issue.

“It’s a serious health concern if even one ingredient is out there that is a new ingredient and has not gone through the NDI process," he said. “The NDI process was created to assure public safety when you bring a new ingredient to market."

FDA has determined certain substances in the marketplace not only haven’t been the subject of an NDI submission, but they don’t qualify as a dietary ingredient and couldn’t be marketed in a dietary supplement even if FDA was notified. One recent example concerns picamilon, which FDA described as “a unique chemical entity synthesized from the dietary ingredients niacin and gamma-aminobutyric acid." Picamilon is the subject of FDA warning letters and a lawsuit filed against GNC by Oregon Attorney General Ellen Rosenblum.

Of the NDI notifications that FDA has objected to, the agency has found 19 percent don’t qualify as a dietary ingredient, FDA’s Naum said.

Mister recommended a dietary supplement manufacturer err on the side of caution if it isn’t sure whether or not to file an NDI. Picamilon highlights the risks posed by not filing an NDI and reflects a “wake-up call to industry" to review its portfolio of products to identify if any require an NDI submission, he noted.

“If you are going to market with an NDI, and you are not going through the notification process," Mister said, “you are not upholding your end of the deal that was struck when DSHEA was passed."

About the Author

You May Also Like