FDA recall data on dietary supplements draws mixed commentary

FDA recall data on dietary supplements drew different reactions from an industry trade group, consumer advocacy organization and Harvard Medical School professor.

Less than 2% of recalls recorded by FDA over a six-month period involved dietary supplements, the American Herbal Products Association (AHPA) disclosed this summer after analyzing the agency's data.

The data provides further evidence of the overall safety of supplements, according to AHPA, a trade group based in Silver Spring, Maryland. But at least one source in the nation’s capital who has criticized the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994 (DSHEA) offered a starkly different assessment, suggesting the data reflects FDA’s failure to adequately police the market.

Fourteen of 803 recalls, or 1.7%, involved supplements, AHPA divulged in an August 2019 report. Of recalls involving supplements, just three were Class 1—the most serious type of recall—according to the report.

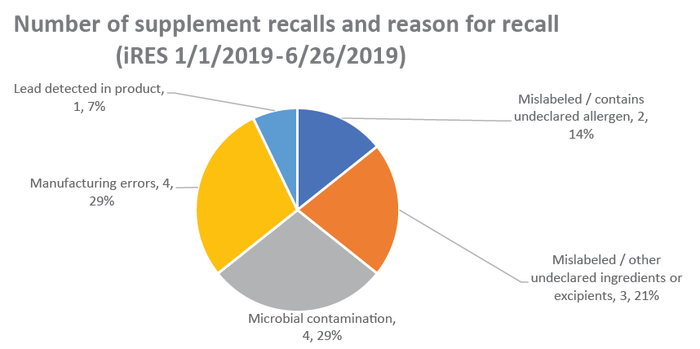

AHPA analyzed internet Recall Enterprise System (iRES) data released by FDA from Jan. 1, 2019 through June 26, 2019.

Of the 803 recalls recorded in iRES, 29% were for medical devices and 28% for biological products, while drug products comprised 18% of recalls and conventional food was responsible for 20% of recalls, AHPA reported.

Supplements had to be recalled due to microbial contamination (29%), manufacturing errors (29%), mislabeling, including incorrect amounts of ingredients and omitted excipients (21%), undeclared allergens (14%) and the detection of lead (7%), according to AHPA.

“These recall data provide additional evidence of the overall safety of the dietary supplement class,” AHPA chief information analyst Merle Zimmermann, Ph.D., stated in the report.

Results from AHPA’s review of other resources—including recorded observations from FDA inspections and mandatory serious adverse event reports—suggested, “current supplement laws and regulations are working effectively to protect consumer safety and ensure a marketplace of high-quality, safe products,” Zimmermann added.

American Herbal Products Association (analysis of FDA recall data)

Peter Lurie, M.D., is a former FDA associate commissioner and the current president of the Center for the Science in the Public Interest (CSPI), a consumer advocacy group in Washington that has raised concerns about many products marketed as dietary supplements and criticized DSHEA, which recently turned 25 years old.

The recall data, Lurie said in a phone interview, “provides no reassurance whatsoever” that supplements are safe. “If anything, it shows how under-policed this whole area is.”

Lurie pointed out FDA’s Office of Dietary Supplement Programs (ODSP) has only around a few dozen employees to police a vast number of supplement products—the total number of which is unknown since manufacturers are not required to list their products with FDA. An FDA spokesperson recently confirmed in an email that ODSP is staffed with 27 fulltime employees.

FDA declined to comment on AHPA’s recall study.

“It’s unsurprising that they (AHPA) would find more recalls in other more heavily policed parts of the agency,” Lurie said.

AHPA regularly requests additional resources to enforce the regulations for dietary supplements, responded its president Michael McGuffin. “But the obvious corollary is, ‘does FDA have 100% of the resources needed to properly enforce all regulations for food'” and other categories regulated by the agency? he asked. “I think it’s unlikely.”

McGuffin also disputed the notion that the need for additional resources “undermines” AHPA’s conclusion that the dietary supplement sector is properly regulated and not imperiling the health of consumers.

“FDA’s pretty smart about using its resources,” explained McGuffin, who added the agency focuses its resources where there are safety concerns.

AHPA’s recall data doesn’t establish supplements are safer than other FDA-regulated categories like conventional food, said Pieter Cohen, M.D., an associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School who has studied products marketed as supplements for several years and identified what he perceives as weaknesses in DSHEA.

The data could mean, for example, that FDA’s ODSP “is not doing its job,” he said in a phone interview. “And that is well supported by prior evidence.”

The other unknown: “We have no denominator,” observed Cohen, who also is a general internist at Cambridge Health Alliance. “How many times do people eat food versus take supplements? If we had a denominator, then you could say, ‘Well, in relationship to having breakfast, a supplement’s safer.’ I don’t know.”

McGuffin pointed out AHPA’s own analysis identified the above limitation in its study and didn’t assert supplements are safer than other FDA-regulated product categories.

“We said that [supplements are] well-regulated, and there’s certainly no evidence that the regulations … [are] missing something,” McGuffin said. “Clearly, the recall data supports the understanding that the current regulations protect the public safety.”

Of the 803 recalls analyzed, AHPA identified seven cases where FDA suggested the products were illegal drugs marketed as dietary supplements and one where the illegal drug was labeled as a conventional food. Those cases comprised 1% of recalls, AHPA reported.

Manufacturers of supplements and the leaders of trade groups—including AHPA, among others—have urged FDA to take swift and vigorous enforcement action against products spiked with undeclared drugs, including working with the U.S. Department of Justice to bring misdemeanor and felony criminal prosecutions. Such products posing as supplements are in fact unapproved new drugs, according to FDA—a distinction supplement trade organizations often make.

In peer-reviewed research published in 2014 in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), Cohen and others identified cases in which products marketed as dietary supplements and containing pharmaceutical ingredients remained available on store shelves long after a recall. Subsequent research published in 2018 identified other instances in which products containing prohibited stimulants in “dietary supplements” remained available for sale following public notices by FDA.

In such circumstances, Cohen said, FDA “rarely, if ever, follows up with a warning letter or other more aggressive tactics to get the products off store shelves.”

Industry, the scientific community and others, Cohen said, have an opportunity to work together to remove dangerous products marketed as supplements.

“The responsible industry has every reason to want consumers to feel comfortable about the products,” he concluded. “We’re not talking about taking any legal supplement off the market. We’re just making sure that everything out there is accurately labeled and as safe as possible.”

About the Author

You May Also Like