Follow FTC guidelines to help avoid trouble from endorsements

Marketers of dietary supplements should follow several federal rules and guidelines when forging relationships with celebrities and others to endorse their products.

A celebrity endorsement on social media has the potential to go viral, boosting sales of a dietary supplement or cosmetic product far more effectively than through traditional advertising. But marketers must apply several principles when forging relationships with endorsers, cautioned lawyers who closely follow FDA and FTC regulations.

“Social media influencers are mouthpieces of the company, so any regulator or possibly class-action plaintiff will perhaps rightly consider anything he or she says to be a statement adopted and endorsed by the company,” said Ivan Wasserman, a partner in Washington with Amin Talati Upadhye LLP, adding that companies should implement “appropriate controls” to “ensure that they have directed the social endorser on what to say [and] what not to say.”

That doesn’t always happen.

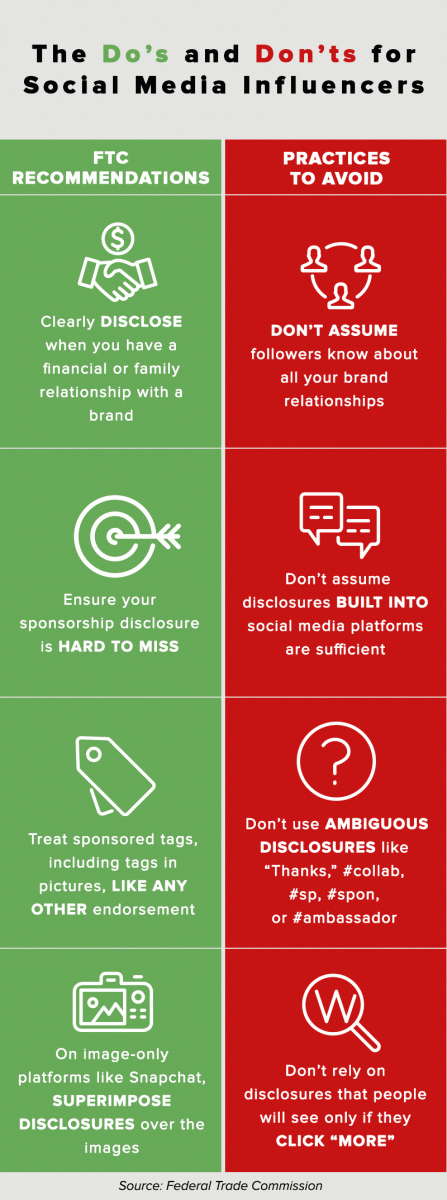

In April 2017, FTC staff sent more than 90 letters to influencers and marketers after reviewing Instagram posts by athletes and celebrities, among others. The letters, FTC observed in a news release, reminded influencers and marketers that “influencers should clearly and conspicuously disclose their relationships to brands when promoting or endorsing products through social media.”

Later that same year, FTC sent follow-up letters to 21 influencers, citing concerns over various social media posts.

FTC has published non-binding guidelines related to endorsements and testimonials in advertising. The guidelines “provide the basis for voluntary compliance with the law by advertisers and endorsers.” FTC in 2017 also published a document that answered questions about the use of endorsements.

“Whether you’re [selling] a weight-loss product or anything else, it doesn’t mean it’s not true, but the FTC says people have to know if there’s a relationship between the endorser and the company so that they can decide what credibility or weight to give to the endorsement,” said Justin Prochnow, a partner in Denver with Greenberg Traurig LLP.

There is a limited exception to making such a disclosure: when the audience expects a connection. FTC guidelines suggest disclosures aren’t necessary when a very famous person—someone “known to a significant portion of the viewing public”— is promoting a product.

Nonetheless, it can be tricky to determine when a disclosure is necessary. Is a YouTube celebrity famous enough to excuse a disclosure? How about a reality TV star on the Bravo network?

In the case of Cindy Crawford, for example, consumers would understand the former model is probably being compensated for a Pepsi television commercial, said Claudia Lewis, a partner in Washington with Venable LLP. But the lawyer said it would be necessary to disclose that an endorser is being compensated if, for instance, an endorsement was made by a famous person who wasn’t considered a household name.

The nature of the disclosure itself raises various questions, especially in an era where social media endorsements have proliferated.

“Is there enough room on that for Twitter?” asked Lewis, highlighting one of the issues addressed in FTC’s endorsement guidelines. “Where does that go? Do you put … the claim first or the ‘compensated endorser’ disclosure first? How does that work? And FTC has some very strong guidelines on what should and shouldn’t be done.”

The industry, she added, “is catching up to what the rules of the road are on that.”

One tidbit of advice for disclosures on social media: Don’t bury them. FTC doesn’t specify where the disclosure should be placed, but the agency examines whether the ad is “easily noticed and understood.”

FTC also suggested disclosures aren’t necessary when an expert is promoting a product if the endorsement relates to an area within the person’s expertise. The agency cited the example of a physician appearing in an ad for an anti-snoring product.

“Consumers would expect the physician to be reasonably compensated for his appearance in the ad,” FTC guidelines noted.

The guidelines, however, added a caveat: a disclosure would be required if, for example, the physician owned a stake in the company or received a percentage of gross product sales since those facts would likely impact the credibility of the endorsement from the perspective of consumers.

Both influencers and brands share the responsibility to disclose their relationship, noted FTC attorney Lesley Fair.

“Influencers should clearly let people know about that connection,” she wrote in a 2017 blog, “and marketers have an obligation to make sure they do—usually by educating their influencers and monitoring what the influencers are doing on their behalf.”

Beyond the question of disclosures, marketers must closely follow what a celebrity or other endorser is saying about its products. That’s because, according to FTC guidelines, “Advertisers are subject to liability for false or unsubstantiated statements made through endorsements.”

FTC raised the example of an advertiser who participates in a blog advertising service and asks a blogger to try a new body lotion. The advertiser does not claim the lotion can cure skin conditions, and the blogger doesn’t ask the advertiser whether there is substantiation to support the claim. (According to FTC, health and safety claims require “competent and reliable scientific evidence” to meet the substantiation standard).

However, FTC guidelines stated the advertiser would be “subject to liability for misleading or unsubstantiated representations” if the blogger asserted in an endorsement that the product cures eczema, and the blogger recommended the lotion to her readers living with the condition.

FTC regulations and guidelines are not the only considerations for marketers when relying on endorsements. Marketers must closely track their endorsers’ statements to confirm they are not running afoul of FDA regulations. In 2015, FDA sent a warning letter to a pharmaceutical company over statements made by reality TV star, Kim Kardashian. On Facebook and Instagram, Kardashian spoke favorably of her use of DICLEGIS during her pregnancy, but she omitted certain information, including the risks associated with the drug.

“The social media post is misleading because it presents various efficacy claims for DICLEGIS, but fails to communicate any risk information,” FDA explained in the letter.

Companies also should be careful when adopting statements about their products made by everyday people even if consumers are not being compensated at all. For example, Prochnow cited ongoing confusion over customer reviews. He uses the following test to determine whether a company should publish a customer review.

“If the company was making the statement, could they say it?” the attorney asked. “And if the answer is no, then the company can’t use that review in their advertising.”

Consider a customer’s statement published on a marketer’s website that a dietary supplement treated a disease. Just because the customer made the statement doesn’t excuse a marketer from the law’s general prohibition against selling a dietary supplement to cure, diagnose, prevent or treat a disease, Prochnow said.

“Once you use it in your advertising, it’s your statement,” he explained.

When republishing a statement by a third party, companies must consider myriad FDA and FTC regulations. Lewis raised the hypothetical of a cosmetic company republishing the statement of a woman who wrote she looked 20 years younger after applying its product.

Is the woman’s experience typical of what consumers generally would achieve from applying the cosmetic? FTC guidelines suggest that’s a crucial question in the analysis. “Does that only apply if you’re using it three times a day and drinking three quarts of water?” Lewis asked.

While the woman has a First Amendment right to say what she wants, an advertiser becomes subject to various rules once it chooses to commercialize her statement, the lawyer pointed out.

FTC guidelines suggested an endorsement would be misleading if it simply said a woman lost 110 pounds in six months by using a weight-loss product accompanied with diet and exercise, when in reality she slimmed down from 250 pounds to 140 pounds through a specific regime of drinking two weight-loss shakes a day, eating only raw vegetables and exercising six hours a day at the gym.

In a sense, the guidelines are bittersweet. They are a reminder to marketers that celebrity endorsements and other testimonials could lead to an FTC investigation and possible lawsuit for deceptive practices. But they also offer many examples for companies to lawfully advertise their products through endorsements, helping to maximize their use of Instagram, Twitter and other social media platforms.

About the Author

You May Also Like