Are Ancient Grains Nutritionally Better?

Genetically speaking, ancient grains haven’t changed much over hundreds of years, which makes them attractive to consumers looking for authenticity. However, their nutrition profiles aren’t much different than traditional grains.

November 21, 2017

The four major grains in use in the world—wheat, rice, corn and sorghum—come from a common ancestor that grew 65 million years ago. Wild cereal grains were discovered from Ohalo II site in Israel. These dated as far back as 23,500 years ago. (Nature. 2004 Aug 5;430(7000):670-3). Agriculture likely began in the dying years of the Ice Age about 11,700 years ago. Evidence of use of sickles to harvest wild barley has been unearthed from the Levant region, according to the Encyclopedia Britannica.

The earliest popular grains in use were modern wheat precursors—spelt, emmer, kamut (Khorasan wheat) and einkorn, along with barley, rye and sorghum. Cultivation initially must have been largely dry land, with crops dependent on rain. Irrigated cultivation is said to have begun in Mesopotamia and China only after circa 5000 BC.

The Whole Grains Council has defined ancient grains to be those “whose roots go back to the beginnings of time." Genetically speaking, ancient grains haven’t changed much over hundreds of years. Modern wheat, corn or rice are not ancient grains. They are an outcome of constant breeding. In the process, their genetic composition has changed.

Barley, black and red rice, blue corn, oats, teff, wild rice and millets are other prominent ancient grains. All these grains come from the same family—Poaceae. Amaranth, quinoa and buckwheat are too often mischaracterized as ancient grains. Many of the ancient grain-based products available on shelves contain some of these grains. Amaranth and quinoa belong to Amaranthaceae, while buckwheat is from the Polygonaceae family. The nutritional profile and their use, though, are like the true grains belonging to the Poaceae family.

Unlike wheat, rice and corn, ancient grains such as sorghum, teff, barley and millets are typically dry land farmed. These are widely cultivated in many parts of Asia and Africa. Millets, sorghum and teff are traditionally cultivated by the poorest farmers who cannot afford access to irrigation, fertilizer, insecticides and pesticides.

In India and Africa, millets, sorghum and teff are consumed more by rural and poorer communities than the wealthier sections of society. The popularity of ancient grains, though, is of late rising. People have begun to believe the grains are healthier compared to hybrid wheat, corn and rice. Farm gate prices of ancient grain are lower when compared to wheat, corn and rice.

There is a wide acceptance that food containing higher fiber content is good for health. High-fiber food helps build a gut environment where good bacteria can proliferate. Foods are labeled high in fiber when they contain at least 5 g of fiber per serving. Many of the high-fiber food products available on the shelves contain fiber supplements artificially added to the product. Bran and other food fibers are popular supplements.

The fiber content of some ancient grains such as barley (17.3 percent), bulgur wheat (18.3 percent) and rye (15.1 percent) is very high. Others, including millet (8.3 percent), oats (10.6 percent) sorghum (6.3 percent) and spelt wheat (10.7 percent) have a fiber content range comparable to that found in whole wheat and corn—12.2 percent and 7.3 percent, respectively (USDA Nutrients Database SR 26, updated September 2013). When grain is debranned to make macaroni, noodles and other products, its fiber content drops to levels ranging from 2.8 to 4.3 percent.

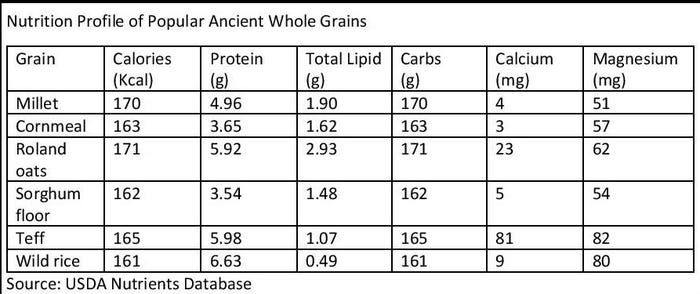

When comparing ancient and traditional grains, one cannot conclude that ancient grains’ nutritional profiles are outright superior. However, some ancient grains such as barley are a rich source of selenium; teff and spelt have high values of magnesium; oats are rich in thiamin; etc. Traditional grains are also rich in some micronutrients. The nutritional content of any grain, though, is affected by the soil and growth conditions.

Careless hulling impacts the nutritional profile. It is not just the bran or fiber that is lost, but the protein layer just below the outer skin of the grain is also damaged. Whole grain or splits should be carefully hulled to protect the fiber coat and the underlying layer of protein. The inner part of the grain is largely starch. It’s no wonder debranned grain and products made from such grain, ancient or otherwise, have a poorer nutritional profile.

Multigrain food products are one approach that works well. They offer a broader range of micronutrients available from different grains. This mix need not be composed only of ancient grains, but can include other grains, too.

The difference between traditional and ancient grain has less to do with nutrition and more with an unaltered genetic profile. Maybe in the future we will discover a biomarker that could be a cure of an untreatable ailment. Until that time, the attraction to ancient grains is probably more a reflection of a desire to look for a superfood: a nutritional El Dorado.

Sudhir Ahluwalia (sudhirahluwalia.com) is a business consultant. He has been management consulting head of Tata Consultancy Services, an IT outsourcing company in Asia; business advisor to multiple companies; columnist and author of the upcoming book “Holy Herbs." He has also been a member of the Indian Forest Service.

About the Author

You May Also Like