Supply chain transparency: A practice of trust through legitimacy, from ‘farm to fork'

The demand and requirements by consumers and regulators for supply chain transparency is at an all-time high and only will strengthen.

How important is supply chain transparency to supplement brands? The level of its importance determines the level of the business’ growth and success. Supply chain transparency builds trust through legitimacy across the board--trust with suppliers, employees, customers and oversight agencies. Are you transparent in the chain? Are others transparent with you? More importantly, how high is the trust level within the chain? Have you ever suspected “deceptive documentation?”

Supply chain transparency is the disclosure and transfer of credible, accurate and truthful information from one supplier to another through the chain of products and services down to the end user. Specifically, in the dietary and food supplement industry, this could mean raw material originating from a farm; shipped or delivered to a raw material supplier or processor, then to a manufacturer; then finished product shipped to a distributor or direct to consumers. A commonly used phrase to describe this chain is “from farm to fork.”

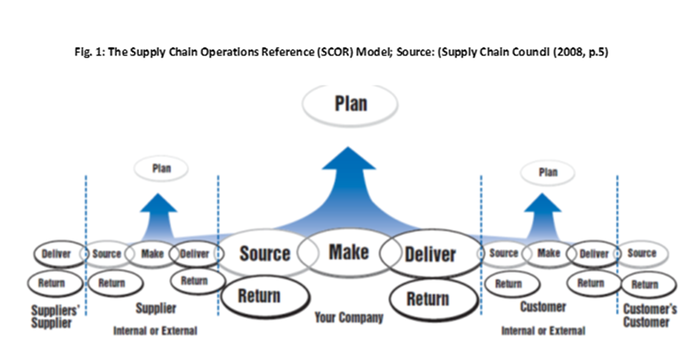

Supply chain transparency is embedded in supply chain management that dates to the early 1900s, according to the supply chain management site SupplyChainOpz. As this network of business evolved, so did the need for dependence on each segment or entity to provide truthful and credible information in order to traverse the continuous flow of exchange of materials and goods through both foreign borders and domestic marketplaces.

The need for supply chain transparency is a demand being placed by consumers who want to know exactly what’s in their supplements, their sources or countries of origin, and how all the associated components were handled and distributed.

Over the last decade, increased attention from regulatory and compliance agencies resulted from a spate of food-safety issues and heightened threat of bioterrorism, as evidenced by the Public Health Security and Bioterrorism Preparedness and Response Act of 2002 (Bioterrorism Act), signed into law by President George W. Bush on June 12, 2002.

As a result, conducting an internet search for information on supply chain transparency today, will result in an overwhelming plethora of information, enough to keep one occupied at length. Whether this represents an emerging trend or a growing corporate awareness of consumer desires might be less debated given the climate of business-related human rights concerns also associated with supply-chain activities (e.g., child labor, forced labor, slavery and human trafficking). Consumers are not the only ones concerned about transparency.

Congress is just as concerned about supply chain transparency, traceability and disclosure requirements demonstrated in the Business Supply Chain Transparency on Trafficking and Slavery Act of 2014 (H.R.4842) introduced by New York State Rep. Carolyn Maloney (D-12). Further, FDA’s enforcement measures have caused the industry to pay more attention to supply chain management and transparency.

Evidence this issue is a priority for the agency is in its existing risk analysis framework and its most recent “sweeping” regulatory enforcement of the Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA); 21 CFR 117 Current Good Manufacturing Practice, Hazard Analysis, and Risk-Based Preventive Controls for Human Food (focus on Part G – Supply Chain Program); 21 CFR Part 1, Subpart L (Foreign Supplier Verification Program [FSVP]); and 21 CFR 11 Current Good Manufacturing Practice, in Manufacturing, Packaging, Labeling or Holding Operations for Dietary Supplements.

Also joining in the nation’s efforts to promote effective supply chain transparency is the U.S. Customs Border Protection (CBP). Attempting to stay current with the challenges of an “evolving trade landscape,” the CBP Office of Trade held an all-day “21st Century Customs Framework (21CCF)” public meeting at the U.S. Department of Commerce on March 1, 2019, to give the public an opportunity to comment on certain aspects of this initiative.

During the meeting, the agency panel heard comments from importers, brokers and other private sector trade stakeholders regarding “Emerging Roles in the Global Supply Chain; Intelligent Enforcement; Cutting-Edge Technology; Data Access and Sharing; and 21st Century Processes.” At the close of the meeting, the CBP panel promised to consider the submitted comments related to intended policy, regulatory and statutory improvements. This action represented a joint “watchdog” effort of products (including dietary supplement ingredients, finished supplement and food products) entering the U.S. borders.

Transparency with regulatory agencies is the “first line” of supply chain transparency. In 2018, the CBP implemented and deployed the core capabilities of Automated Commercial Environment (ACE), the system through which the trade community reports imports and exports and the government determines admissibility.

U.S. and foreign facilities registered with FDA must provide ACE with information necessary for importation of their raw materials and products. This is the first line of supply chain transparency, as it requires that the importer provide credible foreign supplier information and documentation. On the other hand, FDA’s Voluntary Qualified Importer Program (VQIP) is a fee-based program that provides expedited review and import entry of human (and animal) foods into the United States for participating importers. Although companies are not necessarily required to participate in this program, FSMA/FSVP enforcement rules require companies to be transparent, or risk detainment or refusal of goods and raw materials at the border.

Important to understand is that whereas both the CBP and FDA work in conjunction at the border, all FDA regulated products assessed for entry by the CBP is forwarded to FDA; this means the two agencies have separate entry documentation requirements. Compliance with both agencies allows release of the product for entry into the U.S. food supply, according to FDA.

“Blockchain” Technology is the “new frontier” in traceability and transparency in the food ingredient industry. Imagine having private digital or electronic information distributed within the supply chain, but not copied. This is “blockchain,” an emerging trend making its way in the supplement industry, designed to pass on information in a fully automated and safe manner.

Blockchain was originally designed for cryptocurrencies, such as Bitcoin, to transfer money through a list of records, called blocks, which are linked using cryptography.

“Each block contains a cryptographic hash of the previous block, a timestamp and transaction data,” said Thom King, CEO of Icon Foods, in an August 2018 interview with Todd Runestad, INSIDER senior editor. “By design, a blockchain is resistant to modification of the data.”

King briefly explained how this model is applied to the food ingredient industry through “hash keys” that connect each segment of the supply chain and which are verified through the blockchain. Each component within the supply chain would essentially have its own hash-key and that would identify it accurately, inclusive of full disclosure.

King heralded blockchain as the “new frontier” in traceability and transparency in the food ingredient industry. However, a word of caution: blockchain, while still “maturing,” is vulnerable to a new form of cyber-attack known as “cryptojacking.” As this transparency model develops and expands in the industry, companies should look carefully ahead to educating themselves on the appropriate and necessary cyber security, data and intellectual property (IP) protection systems and practices available.

Shari Claire Lewis, a partner at the New York-based law firm, Rivkin Radler LLP, discussed the innumerable risks businesses face in an “online world” with INSIDER’s legal and regulatory editor Josh Long in a September 2016 podcast. She shared important tips for mitigating exposure to data breaches and cybercriminal activity.

Supply chain segmentation is the most effective magnet, as it involves two human elements: communication and interaction with people in the supply chain. Supply chain segmentation is a process or practice by which one-on-one partnerships or relationships are formed by a company, their customers and the various segments of their supply chains (e.g., suppliers, service providers, co-manufacturers or employees). It is the “dynamic alignment of customer channel demands and supply response capabilities, optimized for net profitability across each segment,” according to a report from Chalmers University of Technology in Sweden.

The people who are within each of the supply chain segments are key, from employees who represent the critical support of a company and suppliers who deliver the raw materials to the end customer, whose trust each brand owner must win.

Heather Fairman is an independent consultant with EAS Consulting Group LLC (easconsultinggroup.com) and serves as Technical Advisor for the SIDS DOCK Island Women Open Network (IWON, sidsdock.org), an intergovernmental organization of Small Island Developing States (SIDS). With almost 30 years of combined quality assurance (QA)/quality control (QC) and regulatory experience gained from FDA-regulated industries, Heather applies her regulatory perspective and approach toward handling FDA matters and compliance requirements relative to all aspects of cGMP (current good manufacturing practice) and development of contract partnerships to ensure mutually beneficial and compliant outcomes.

About the Author

You May Also Like