A primer on mushrooms with Nammex’s Bill Chioffi

In this two-part Q&A column, Nammex Chief Strategy Officer Bill Chioffi discusses all things mushrooms.

Natural Products Insider: What defines a mushroom?

First, it might be helpful to revisit the taxonomic classification system we were taught in grade school science class. Mushrooms are part of the biological kingdom “Fungi” and therefore distinct from plants and animals.

Most mushrooms are composed of a cap and a stem. The underside of the cap has many thin blades called gills that are the spore-bearing surface. Spores are the “seeds” by which mushrooms can spread to new areas.

The shiitake (Lentinula edodes) is an example of the classical mushroom shape. Not all mushrooms are so classically formed or even edible. Polypores, the group to which reishi (Ganoderma lingzhi) and turkey tail (Trametes versicolor) belong, do not have gills, in many cases lack a stem, and they are hard like the wood they grow on. The underside of a polypore cap is composed of a tightly packed layer of pores where the spores are propagated.

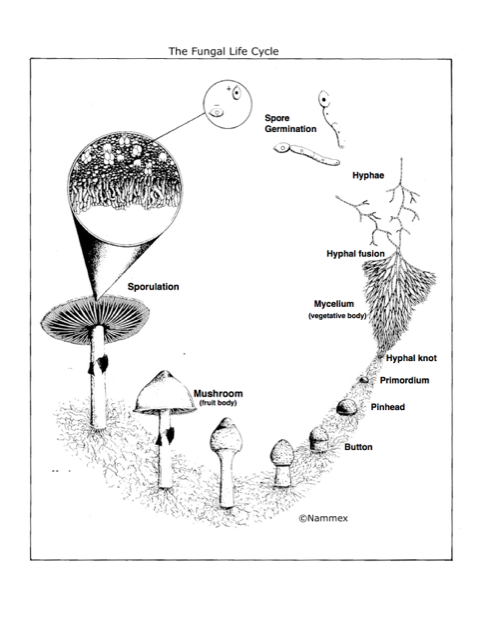

To fully define mushrooms and mushroom products, an understanding of their life cycle is helpful.

A mature mushroom produces billions of spores, most of which are carried away by the wind. If someone performed air-quality testing and examined the number of total fungal spores present in an indoor or outdoor environment, they would observe people are literally being covered in these microscopic spores. In other words, humans are interacting with these microscopic spores all the time, whether they like it or not.

What is not readily visible, however, is the fungal vegetative body, called mycelium. Just as an apple is the fruit of an apple tree, so too is a mushroom the fruit body of a mycelial “tree.” Mycelium is a network of fine threadlike filaments that originates from the germination of spores.

Unlike green plants that convert sunlight into energy, fungal mycelia generally derive their nutrients from dead organic matter, like leaves, annual plants, and wood waste, recycling this material into humus, the organic material that forms in soil when plant and animal matter decays. As the mycelia spread throughout the nutrient base or substrate, they are amassing nutrients. While mushrooms can readily be observed, the mycelial network generally stays hidden within the nutrient base materials.

When environmental conditions are suitable, the mycelia use these nutrients to produce mushrooms, which are sometimes referred to as a “fruiting body.” At this point, the life cycle is complete, as a new generation of mushrooms mature and spread spores into the environment.

It’s also interesting to note that the mushroom has been consumed as a food and medicine since recorded history.

(Graphic above provided courtesy of Nammex)

Natural Products Insider: Where are most mushrooms grown?

Mushrooms utilized as nutritional supplements are rarely cultivated in North America. It’s just too expensive. The fresh mushroom, which consists of 90% water, has to be dried and then must be processed for extraction. Most mushrooms today come from Asia, primarily China. In fact, China produces 85% of the world’s mushrooms. Even Japan, a traditional mushroom producer, is the No. 1 importer of Chinese mushrooms.

Many of the world’s foremost experts in everything related to mushrooms, including cultivation, are in China, which has a long history of mushroom use in foods and medicines. Nammex has sourced our organic extracts from China for over 25 years from farms located deep in the mountains and far from industrial pollution. In fact, in 1997, Jeff Chilton organized the first organic certification workshop for mushrooms in China. We can attest to the extraordinary cultivation skill of our farming partners as well as the breadth and depth of knowledge of our Chinese scientific colleagues.

Natural Products Insider: What’s the difference between mycelium on grain (MOG) and mushrooms?

A mushroom and its mycelium are made of similar tissue, but with important differences. Mushrooms are genetically more complex and produce a greater variety of medicinal compounds than mycelium.

MOG is what commercial mushroom growers call “grain spawn,” which is the seed to grow mushrooms. The manufacture of grain spawn is highly mechanized, and it is inexpensive to produce, unlike mushrooms, which are still harvested by hand. The fully colonized blocks of myceliated grain are simply dried and milled into a powder.

However, mycelium grown on grains contain far less of the same constituents found in other parts of the organism above the ground that we know as a mushroom. While MOG is inexpensive, it contains relatively small amounts of mycelium and is mostly grain. It is very similar to the food product called tempeh. Due to the high amount of grain starch, MOG has significantly lower active compounds compared to mushrooms. Therefore, MOG poses formulation challenges in delivering enough actives to provide similar health benefits as those contained in mushrooms.

Editor’s note: Part II of this mushroom series with Nammex Chief Strategy Officer Bill Chioffi will cover the meaning of a “full-spectrum mushroom product,” differences between a mushroom powder and an extract, how fungi should be labeled in dietary supplements based on federal requirements, and more.

Bill Chioffi is the chief strategy and innovation officer for Nammex, a manufacturer of certified organic medicinal mushroom extracts. Bill's 30 years of experience in the production and sale of botanical medicine encompasses retail, manufacturing, and food and beverage sectors. Bill worked for Gaia Herbs for 21 years, exiting the company as vice president of global sourcing and sustainability, and more recently as the vice president of strategic partnerships and business development for the Ric Scalzo Institute for Botanical Research at Sonoran University of Health Sciences. Current board positions include AHPA (American Herbal Products Association), United Plant Savers, and the Sustainable Herbs Program.

About the Author

You May Also Like