Supplement maker subject to massive recall was GMP-certified

Two prominent industry GMP programs certified or registered the contract manufacturer at the heart of a massive recall prompted by a federal injunction for GMP noncompliance.

Two well-known industry cGMP (current good manufacturing practice) programs certified or registered ABH Nature’s Products Inc., a New York-based contract manufacturer of dietary supplements, during the time frame included in a massive recall due to GMP noncompliance and which consultants have described as “unprecedented.”

One program involved standards from the first dietary supplement GMP certification program, the other was launched by the only independent certification organization accredited by the American National Standards Institute (ANSI) to test and certify dietary supplements.

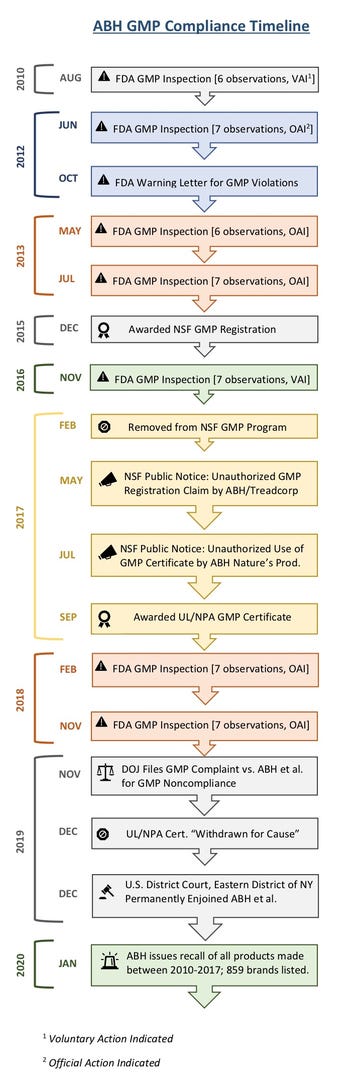

ABH’s certification through the Underwriter Laboratories (UL)/Natural Products Association (NPA) and registration in NSF International GMP programs stand in stark contrast to the contract manufacturer’s long history of alleged GMP violations based on FDA inspections.

“This certainly was a bit of a hiccup,” said Dan Fabricant, Ph.D., CEO and president of NPA, referring to the GMP certifications previously awarded to ABH.

ABH Nature’s Products Inc., ABH Pharma Inc. and StockNutra.com Inc. (collectively “ABH”) issued an “unprecedented” recall of dietary supplements in January 2020 following a federal injunction due to cGMP violations. ABH listed 859 entities in the recall notice. ABH recently removed its customer list from the initial recall notice as the company works to refine it.

ABH did not respond to Natural Products Insider’s numerous requests for comment on the recall.

Prompted by FDA, the Department of Justice (DOJ) filed a complaint against ABH Nature’s Products and affiliates on Nov. 21, 2019.

“In particular, the complaint alleged that the FDA had observed several critical deviations from current good manufacturing practice regulations during its inspections of ABH’s manufacturing facility, including failures to verify that certain dietary supplements met the product’s specifications for identity, purity, strength and composition; to implement a production system that ensured the quality of the supplements; to include necessary information in its production records; and to properly review and investigate a consumer complaint,” DOJ stated, in a press release.

These violations rendered products manufactured by ABH misbranded and adulterated, DOJ stated.

“I think everyone's happy about the message that FDA is clearly taking GMPs as seriously as they take any other adulteration charge,” Fabricant said, in an interview.

He led FDA’s Division of Dietary Supplements (since elevated to Office of Dietary Supplements Programs) from early 2011 through early 2014.

“For years and years, both internally and externally, I heard, and never liked, that GMP [noncompliance] was considered a technical violation,” Fabricant said.

However, FDA has faced much criticism over how long it took the agency to bring advanced enforcement against ABH, given FDA inspections spanning 2010 to 2017 resulted in numerous alleged cGMP violations and a warning letter in October 2012. Following several inspections, FDA recommended regulatory and/or administrative action against ABH, FDA records show.

Many stakeholders have asked how a company like ABH could earn top industry GMP certification after such violations and a warning letter.

A big miss?

“It’s important to remember that GMP audits are a snapshot of a moment in time,” noted Kenneth Cloft, business unit manager of certifications at NSF, via email. “ABH [Nature’s Products] met the requirements for good manufacturing practices registration beginning in December 2015 and was no longer listed under that registration as of February 2017.”

David Trosin, managing director of health sciences certification at NSF, told Natural Products Insider that NSF is unable to comment on the specifics of an audit, certification or registration, beyond providing dates of that certification or registration.

In his email, he noted upon the expiration of ABH’s certificates, NSF notified ABH Pharma that its use of the certificate was unauthorized. In the interest of public health and transparency, NSF issued a public notice in July 2017, advising ABH Pharma Inc. was falsely advertising its products as certified by NSF International and QAI (Quality Assurance International), and claiming product was manufactured in an NSF GMP registered facility.

Natural Products Insider further found a public notice issued by NSF in May 2017, warning of unauthorized use of NSF registration claims by ABH in conjunction with Treadcorp Ltd., which was among the brands listed in the recall.

“The corporate entity ABH/Treadcorp is not, and has never been, GMP registered by NSF International and is not authorized to make claims of NSF GMP registration,” the notice stated. Cloft clarified ABH Nature’s Products was once registered, but the entity ABH/Treadcorp was not.

In September 2017, UL issued ABH certificates of conformance under the UL/NPA GMP program This allowed ABH to use the co-branded UL/NPA logo for GMP certification.

NPA created its dietary supplement GMP program in 1999, about eight years before FDA issued its final rule on supplement GMPs in 2007, after which NPA amended its GMP program. NPA and UL came together in 2014 to offer supplement GMP education, and the pair formed a licensing partnership on a GMP certification program in 2015.

Under the agreement, UL conducts the audits of ingredient and finished products in accordance with 21 C.F.R. 111—the cGMPs applicable to dietary supplement manufacturers—and the NPA Standard for dietary supplements as well as ICH Q7A and NPA’s Program for Ingredients.

“This certification is significant because it is yet another trusted source under their belt that determines that the processes they use to manufacture your supplements are in conformance with GMP Dietary Supplement CFR 21 Part 111 standards,” ABH said, in a November 2017 press release.

These certificates were due to expire in September 2020, but UL confirmed, via email, ABH’s certificates were “withdrawn for cause” on Dec. 18, 2019, eight days before DOJ issued its press release on the ABH injunction.

UL declined to comment further on the specifics behind the certification withdrawal.

“I don't know all the reasons for [the withdrawal],” Fabricant said. “I believe it's because they became aware of the FDA action. However, there was FDA action dating back to—I can say this confidently as we sent a warning letter when I was at FDA—2012.”

UL cannot comment on the FDA situation, as it was not privy to all the information behind FDA’s actions, according to Michelle Press, the company’s communications director. “We can say UL follows the NPA GMP program requirements and administers the certification program in accordance with industry recognized standards for the accreditation of certification and inspection bodies including the ISO/IEC 17065 and ISO/IEC 17020 standards,” she noted, via email.

Both UL and NSF assured their respective certification programs include vetting the regulatory history of applicants.

Press said in addition to auditing factories where the products are being manufactured to confirm the manufacturer conforms with the relevant cGMP standards, the UL program includes a review of FDA reports and corrective action plans.

“As part of the audit process, we will ask for corrective actions on nonconformance as needed and also take more strict action when program requirements are violated, including withdrawal of the certification, as was done in this case,” she explained, referring to the ABH withdrawals.

Cloft said NSF’s processes require a full review of prior regulatory enforcement activities prior to allowing a company into the program.

“However, prior regulatory enforcement actions do not automatically disqualify a manufacturer from seeking GMP registration as part of a continuous improvement program,” he countered. “We wouldn’t want to exclude companies that are legitimately trying to improve the quality of their manufacturing practices.”

According to the inspection and actions timeline provided by FDA’s Data Dashboard, ABH had several observations—GMP conditions the agency deems objectionable—for FDA inspections in 2010 and 2016; FDA classified these inspections as voluntary action indicated (VAI), which means the agency is not prepared to take or recommend any administrative or regulatory action despite the “objectionable” observations. However, inspections in June 2012, May and July 2013, and February and November 2018 each generated six or seven observations for alleged GMP violations. FDA classified these inspections as official action indicated (OAI), which means regulatory and/or administrative actions will be recommended.

ABH’s period of NSF GMP registration came between FDA’s 2016 and 2018 inspections. The November 2016 inspection resulted in seven observations, but industry regulatory experts have questioned this lesser designation. According to FDA Data Dashboard, these observations included failure to conduct identity testing, to verify finished product batches met product specs and to qualify a supplier to verify certificates of analysis (CoAs), as well as several failures by quality control (QC) personnel to conduct material reviews to ensure products weren’t adulterated and to reject out-of-spec product.

In the procedures outlined on NSF’s GMP supplement program website, the firm conducts facility audits and corrective action report (CAR) processes twice annually. NSF removed ABH from its program roughly three months after the company’s November 2016 FDA inspection.

The path ahead: Lessons learned

“The agency found something that the certifiers didn't, and that kind of defeats the point of certification, right?” Fabricant lamented. “That's ultimately the message that gets conveyed, and we don't want that to be the message.”

He noted ABH has not been a member of NPA since 2010, which should exclude them from bearing the NPA GMP mark. However, he added this is no time to nitpick and assign blame, and he said the certifiers do good work.

Still, “there’s got to be some uniformity,” Fabricant advised. “You must have an independent body outside of the certifiers.”

He held up the food industry’s Global Food Safety Initiative (GFSI) as a prime example and suggested the supplement industry support a structure like that of the Supplement Safety & Compliance Initiative (SSCI), a retailer-led initiative to provide quality assurance (QA) from harvest to retailer shelf.

“We have to have benchmarking,” Fabricant stated. “Whatever the certification is, it's got to have a standard meaning that these sorts of things [ABH] don't get missed.”

UL said it stands by the integrity of its GMP certification process, but it supports industry harmonization efforts such as SSCI “to improve systems and benchmark against leading standards designed to improve competency of auditors and effectiveness of certification schemes specifically within the dietary supplement value chain.”

Cloft noted NSF regularly updates its programs, policies and audit checklists for consistency with cGMPs, regulatory requirements and industry best practices.

“The 173 GMP audit for dietary supplements has been significantly updated, and all clients have been audited to that version as of December 2019,” he reported. “We are also in the process of launching NSF/ANSI 455-2, which is a further update to the program that will be ANSI accredited.”

Further, as of January 2019, NSF currently has a risk-based grading system, according to Cloft, which allows NSF to audit facilities that have more severe findings—from NSF or FDA—more frequently and those with fewer and less severe findings on an annual basis.

“Previously, audits were performed biannually,” he confirmed. “Under the current program, the typical dietary supplements facility is audited for at least three days once per year, with many undergoing further verification audit days. Any facility that does not receive its next required audit is removed from listings and notified to cease use of any marks or certificates that represent registration. It is always best practice to verify the compliance of any facility by checking the listings page of the appropriate certification body to confirm that the certificate provided is valid and still in effect.”

Obtaining timely access to FDA 483 inspection reports can prove challenging, possibly making it harder for a third-party organization to fully understand a company’s regulatory history. Fabricant noted 483 reports are not always made public.

Clearly, the certifiers saw something amiss when they kicked ABH out of their programs, he reasoned, but it is possible they did not know about the prior 483s or they weren’t available via a Freedom of Information Act request.

The company would also have been required to disclose earlier 483s and GMP compliance issues, Fabricant said, but he had no knowledge if ABH did so. Both NSF and UL declined to provide specifics.

For now, NPA said it is reaching out and offering help to certifiers and companies affected by ABH.

“Certifiers might not like hearing this, but their role as a third-party service provider is not to set standards,” he said. “Their role is to ensure they have auditors that meet the standard. It is really the industry's role, and this is where SSCI comes in, to interface with the agency for agreement on what that standard is. That's how it has worked for food safety with GFSI, and I think that, ultimately, that's where we need to aspire to be.”

SSCI just finished its benchmarking, a big initiative, Fabricant said.

“We need certifiers to measure up to that benchmarking document,” he continued. “Until that happens, unfortunately, we're vulnerable for more things like what happened in ABH. Again, we don't want that, and I don't think the certifiers want that either.”

About the Author

You May Also Like